Por Elton Alisson - Agência FAPESP – 24 de julho de 2024 - Animais encontrados em…

Crise na reciclagem da Califórnia destina milhões de garrafas e latas para os aterros

Os baixos preços pagos pela sucata está tirando recicladores do mercado.

Matérias primas mais baratas e menor demanda chinesa por garrafas e latas usadas tem abalado a indústria da reciclagem.

700 dos cerca de 2.400 centros de triagem de materiais recicláveis já foram fechados na Califórnia.

California’s Recycling Crisis Sends Billions of Bottles and Cans Into Landfills

Low prices for scrap are driving recyclers out of business.

About 90 percent of the 8 billion soda cans sold in California every year get turned in for recycling and a 5¢ refund. But cheaper commodity prices, plus lower Chinese demand for America’s used bottles and cans, have upended the economics of the state’s recycling industry. Over the past two years, California’s recycling rate has fallen enough to relegate more than 2 billion containers a year to landfills.

About 700 of the 2,400 redemption centers California had in 2011 have closed, according to CalRecycle, the state’s recycling agency, the majority in the past year. The mostly small companies that run the shedlike centers in parking lots outside grocery stores are being squeezed by a commodity bust that’s lowered the price they receive for recycled glass, plastic, and aluminum. The price they have to pay consumers for this detritus has stayed fairly high. A state subsidy program that was supposed to help make up the difference hasn’t kept up.

In most of the 10 states with bottle redemption laws, beverage companies such as PepsiCo pay recycling centers a fixed amount per bottle, which means the centers don’t need to rely on the market value of the scrap. In California, the state pays redemption centers for processing and handling recycled material. The centers also make money by reselling bottles and cans on the scrap market. Twice a year, California sets a minimum price that redemption centers have to pay consumers for their bottles and cans; it’s supposed to equal the deposit customers paid when they bought the drinks. This year, that’s $1.57 per pound for aluminum cans, down 2¢ from last year, and $1.19 a pound for plastic bottles, up 3¢.

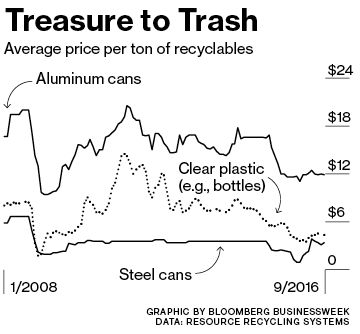

Scrap prices have fallen much more. As of September, a ton of sorted aluminum cans went for $11.88, down 28 percent from two years prior, according to Resources Recycling Systems, a consulting company in Ann Arbor, Mich. A ton of plastic bottles went for $4.25, down 44 percent since 2014. Lower oil prices have also cut the value of recycled plastic, by making it cheaper than it was before to manufacture new plastics, and in some cases it’s cheaper than buying recycled materials.

The decline in the value of scrap is draining California’s Beverage Container Recycling Fund, which relies on the proceeds from bottle deposits consumers pay upfront to reimburse redemption centers. As of June 30, it had $195 million, down from $246 million a year earlier. At this rate, it’s expected to run out of money in the first half of 2018.

“There’s been a massive crisis and a massive failure to respond to that crisis,” says Susan Collins, president of the Container Recycling Institute, an advocacy group in Southern California. Collins says the state needs to boost its “outdated” payment formula by as much as $1 million a month or follow other states, where bottling companies pay recycling centers a fixed amount per container. A spokesman for CalRecycle says the state is looking at all options.

China is the largest destination for U.S. scrap exports, taking about 11 percent by volume in 2015. Since 2013, under a government program called Operation Green Fence, China has been aggressively inspecting and in some cases turning away bottles and cans that are mixed in with food waste or other nonrecyclable scrap. The policy has forced waste processors in the U.S. to screen discarded containers more carefully, driving up costs and diminishing the value of some waste.

Since his local recycling center closed last year, Hiro Tani, a cook who lives in Santa Cruz, has had to take his used bottles and cans to a facility about 15 miles away. “It kind of defeats the purpose if you have to drive that far,” he says. Jose Ponce, who operates six centers in the Los Angeles area, says he’s struggling to keep his business open amid lower scrap prices. “If it keeps going the way it is, I don’t know if I’m going to make it,” he says. “That would be bad for the environment and also bad for people.”

Waste Management, the top U.S. waste processor, has closed about 20 percent of its processing facilities nationwide in the past two years, says Brent Bell, vice president for recycling operations. “If you told me today that China’s GDP growth rate was going to go back to 14 or 15 percent and the price of oil would go back to $100 a barrel, I would say we would go back to where we were. I don’t see those two things happening.”

The bottom line: About 30 percent of California’s recycling centers have gone out of business amid falling prices for scrap aluminum, glass, and plastic.

Fonte – Bloomberg

Boletim do Instituto IDEAIS de 17 de outubro de 2016

Instituto Ideais

www.i-ideais.org.br

info@i-ideais.org.br

+ 55 19 3327 3524

Este Post tem 0 Comentários